Fred Tee left the factory at the end of the day and walked home, just like everybody else.

But unlike everybody else after dark he snuck back into the factory.

Fred Tee had a secret. A secret no one else would know for another 30 years.

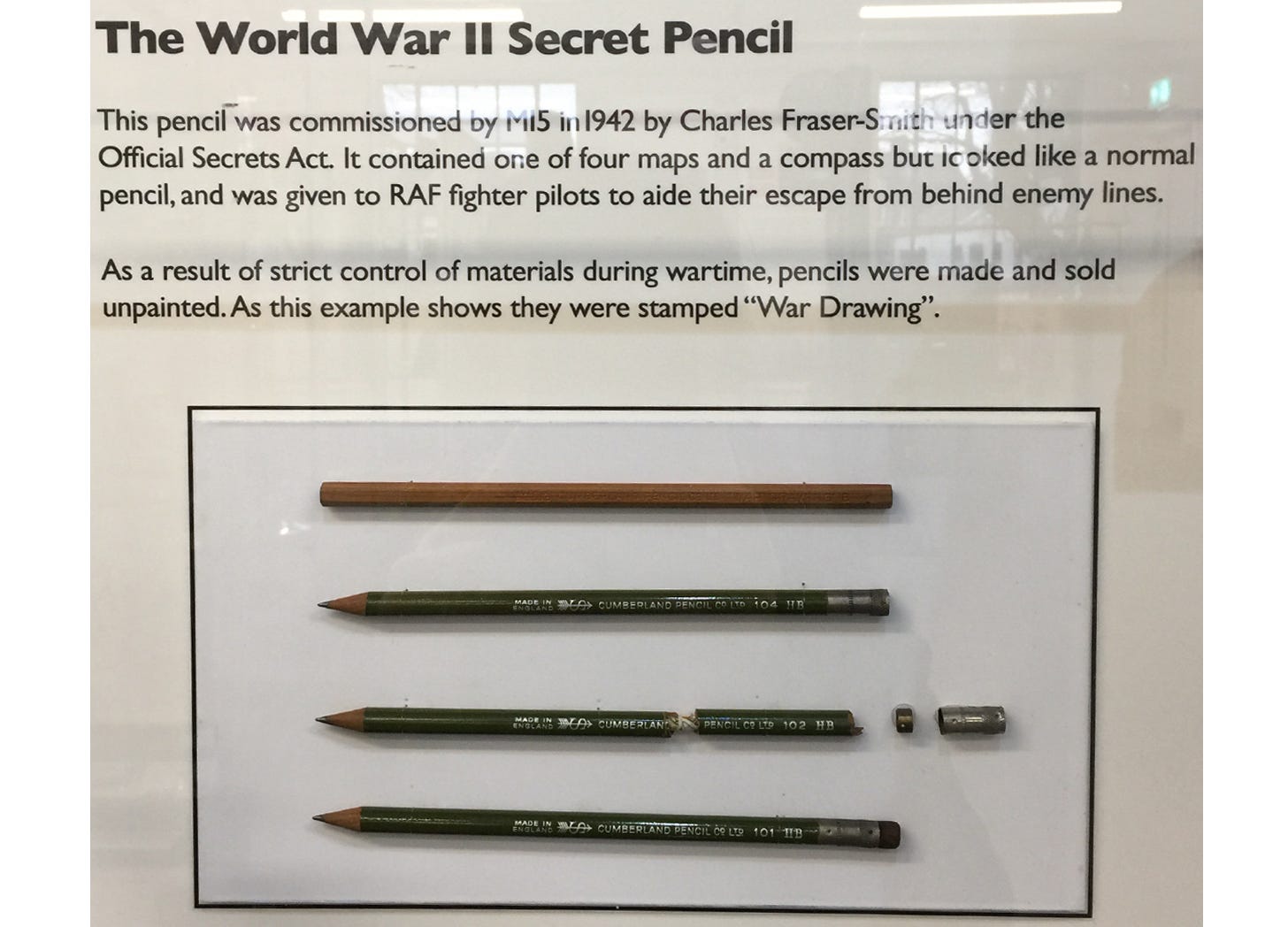

It was 1942 and Fred Tee was the technical manager at The Cumberland Pencil Company, the oldest manufacturer of pencils in Britain. He was approached by Charles Fraser Smith from the The Ministry of Supply.

Except, Charles Fraser Smith was really from MI5.

And he needed Fred Tee’s help to provide details of escape routes to prisoners of war and airmen lost behind enemy lines.

Because of the Geneva Convention prisoners of war were allowed to receive packages from aid organisations. These typically included things like packs of playing cards and pencils.

Pencils were also among the standard kit issued to airmen.

Who would pay attention to a simple, ordinary, everyday pencil?

Charles Fraser Smith, that’s who.

Fraser Smith’s idea was to manufacture a pencil that could be broken open to reveal a hidden map and compass.

He needed the skills of the country’s most established pencil makers. Fred Tee and a select group of employees at the Cumberland Pencil Factory signed the official secrets act and got to work.

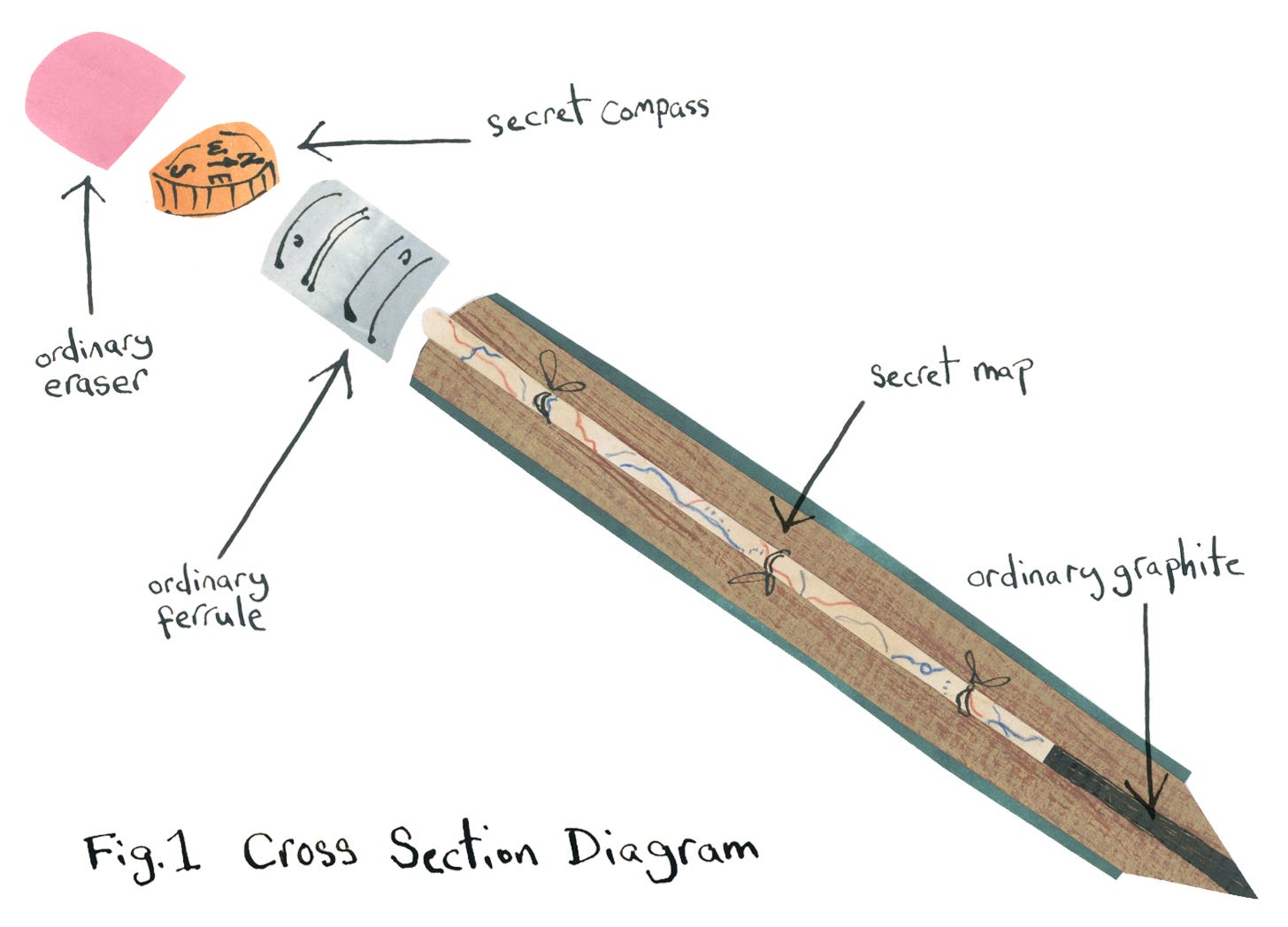

After the factory shut at night they would take a completed box of pencils, then drill out the inside of each pencil, leaving a short length of lead at the sharp end. A 12cm long map was rolled tightly and inserted into the centre of the pencil. The metal ferrule of the pencil was attached and a tiny 8mm diameter compass slipped inside. Then an eraser was glued to the end.

From the outside it looked like an ordinary pencil.

There were four different maps, each detailing a different escape route. A code was stamped on the outside of the pencil, identifying which map was hidden inside. During the war most pencils were sold unpainted but the secret pencils were given a coat of green paint, to ensure they were the ones sent where they were needed.

If you have a pencil to hand, feel free to take a moment and look at the diameter of it’s lead. How did they fit a map into that space?

The map had to be printed on a material that was very fine and thin as well as durable, water resistant, crease proof and most importantly didn’t rustle.

Initially the maps were printed on pure silk, but that was was needed for parachutes. So a paper was made from Japanese Mulberry leaf. This was thin enough to see through but held printed ink well. It could be dipped in water, was crease resistant and most importantly did not rustle.

Charles Fraser Smith commissioned a London company that made large compasses for the Royal Navy to create a compass tiny enough to fit under a pencil eraser. These were then secretly delivered to The Cumberland Pencil factory.

After the second world war ended, all record of the project was sent to the British government to be destroyed, this included all completed pencils still at the factory, all remaining components, and all written records about their construction.

The story of Fred Tee, Charles Fraser Smith and the secret pencils made at The Cumberland Pencil Factory was only made public in the 1970’s. Their story is commemorated at The Keswick Pencil Museum in Cumbria.

Today, The Cumberland Pencil Factory is known as Derwent.

Perhaps you have one of their more ordinary pencils?

All my posts are remaining free and open for the foreseeable future! If you fancy getting me a cuppa tea that would be amazing! Totally up to you, we’ll still be friends!

Sources:

Two visits I made to the Derwent Pencil Museum

How the humble pencil assisted in WW2

New Scientist - part of this article anyway - flipping paywall

Trip to Derwent Pencil Museum Keswick

Cumberland Map Compass Pencil of WW2

Charles Fraser Smith on Wikipedia of course

This is AMAZING Nanette! What a fabulous story! Are you going to turn it into a children’s book? X

You should definitely do a secret pencil book! That pencil really captured my imagination too at the marvellous Pencil Museum!